Fires claim a smaller and smaller share of American lives with each passing decade. Political figures and fire chiefs have played their part—often as a reaction to catastrophic events—but in large part, the credit for the standards protecting people, homes, and businesses from hazards belongs to the fire insurance industry.

The National Fire Protection Association (NFPA), one of the nation’s most influential fire-prevention groups, emerged from the need to keep insurers from going bankrupt—and made a safer world in the process. To learn about the enormous influence the NFPA exercises on your everyday life and how you can be part of the process, read on.

NFPA is Born: History of Early American Fires

The earliest home fires in American history couldn’t be stopped so much as contained. Entire neighborhoods delayed the inevitable, dumping water, bucket by leather bucket, on the flames. By the Civil War, each city might have several fraternities of volunteer firefighters, some with horse-drawn or steam-powered pumps, who salvaged what they could and prevented the spread of fire to nearby homes.

Early Days of Fire Protection (Image Source)

When these fires devastated entire regions—as they did in Chicago and Boston—insurance companies collapsed with them. 200 fire insurance companies did business in Chicago during the Great Chicago Fire of 1871; after nearly 18,000 buildings burnt down, more than 60 of those companies went bankrupt, leaving insured homeowners with less than half of what they were owed.

The insurance industry recovered and spread to new cities and the American West. But as they offered policies in more and more areas, they ran into a problem: the way cities and buildings were built varied, and with that variation came risk. Automatic sprinklers had existed for decades, but standards for the piping and placement varied even within a given city. That’s if they were installed at all. Worse yet, fire engines would arrive at a home only to find that they couldn’t connect their hoses to local hydrants.

With profits at risk, insurers turned their focus toward setting a uniform set of standards for fire prevention.

Enter the National Fire Protection Association, or NFPA.

NFPA Expands: The Campaign to Stop Fire Everywhere

NFPA Logo (Image Credit)

In the wake of devastating fires and severe economic downturns, insurance agencies learned to collectively gather and analyze fire risk on a large scale. At the turn of the 20th century, a handful of these insurers formed the NFPA, applying what they’d learned to the task of reducing fire risk. By the 1910s, the NFPA had developed and distributed hundreds of thousands of copies of their standards—covering fire sprinklers, hydrants, building design and more—free of charge.

Little changed. The number of fires increased and so did insurance losses. City by city, the NFPA reached out (PDF) to mayors, fire chiefs and the public to make them aware of fire hazards. They investigated the major fires of the following decades and published their findings, becoming a leading authority in the field of fire prevention. As they grew, they reported on and created standards for an ever-growing list of topics, standardizing safety measures in automatic sprinklers, movie theaters, the handling of hazardous chemicals, airplanes, and laboratories.

In many cases, the NFPA’s code isn’t the only option for governments looking for pre-made standards. Even when it is, local governments usually can choose from several editions of existing code. Codes published by the NFPA aren’t law, but government entities have gradually given them legal power. Through a process called incorporation by reference, governments point to specific standards—for example, a sprinkler installation code from 2009—and make them mandatory.

Today, the NFPA maintains a government affairs office with regional directors for all 50 states and Canada (See entire list here). Presidents and Congress have made the use of these standards more popular by directing federal agencies to use these and other codes rather than write their own regulations.

They’ve been wildly successful in making code uniform throughout the country. Two codes—the National Electric Code and Life Safety Code—have been made law in almost every state (PDF). When you’re choosing a circuit breaker, covering an outdoor outlet, or walking toward a lit exit sign, it’s likely an example of an NFPA code in action.

NFPA Everywhere: U.S. Building Codes

More than 300 NFPA codes exist today. Each contains a sizable collection of recommended practices that influence the work and safety conditions of contractors, facilities managers, builders, medical workers, and a long list of others. These codes cover a lot and change often.

| Code | Name | Why it Matters |

| NFPA 1 | Fire Code | It’s all about designing safer buildings and keeping them safe: inspection, firefighter training, and much more |

| NFPA 10 | Standard for Portable Fire Extinguishers | Fire extinguishers need to be right for a building’s hazards and easy to access in an emergency |

| NFPA 13 | Standard for the Installation of Sprinkler Systems | The design and installation of sprinkler systems mitigates and slows a fire’s progress, making it one of the most effective fire suppression tools on the market |

| NFPA 14 | Standard for Installation of Standpipe and Hose Systems | Fighting fires without water is tough; Standpipes and hose guarantee a reliable and accessible water supply during an emergency |

| NFPA 70 | National Electrical Code | The go-to standard for minimizing electrical risks |

| NFPA 101 | Life Safety Code | Buildings old and new can facilitate a safe exit |

Select NFPA codes pertinent to fire safety

Let’s look at the way the NFPA’s standards for sprinkler systems, standpipes, and hoses impact you.

Sprinkler system standards span several volumes. NFPA 13 covers the installation of sprinkler systems in commercial buildings. NFPA 13D applies to one- or two-family dwellings, while NFPA 13R covers low-rise residential occupancies (such as apartment homes, townhomes, and condominiums under a particular height). The NFPA crafts these standards to ensure that sprinklers meet minimum design standards, have enough pressure and discharge soon enough to minimize damage to people and property.

NFPA Code Books (Image Source)

NFPA 13, the industrial standard, works to prevent property damage by fire. In contrast, NFPA 13D, the standard for the average home, exists primarily to save lives. 13D’s standards are lax by design: systems meeting these standards are meant to be affordable, encouraging widespread adoption of residential sprinkler systems in homes. Sprinkler systems can be built using domestic plumbing, and home pumps and water tanks aren’t subject to the benchmarks established in other volumes. There’s a good reason for that the NFPA to pursue these policies: 90% of fire deaths occur in residential areas, and a cost-effective sprinkler system might be widely adopted, saving lives. If you want to learn more about the NFPA 13 family, read our blog: The History of Life Safety Code: NFPA 13, 13D, and 13R.

Let’s turn to NFPA 14. Among other things, this code provides for minimum water pressure for standpipes, which serve as something like fire hydrants for large buildings. NFPA 14 establishes standards for hoses and standpipes, which are critical for first responders and fire suppression crews faced with fires at high-rises, commercial and industrial buildings, subways, and anywhere else large numbers of people gather.

These standards classify buildings and establish which hose connectors are needed, how much water pressure is necessary, and the kinds of signs to be posted nearby. These systems exist to provide rapid access to water throughout a large building. That’s nothing to take for granted when maintaining enough water pressure in the upper floors of a skyscraper or an apartment complex. These standards also provide for the installation of pressure-reducing valves, which make sure that the excess pressure used to deliver water to the 50th floor doesn’t interfere with firefighters’ efforts on the third floor.

NFPA: Private Group, Public Law – Who Decides What’s Safe?

A former NFPA president described the organization as “a creature of the fire insurance business”—run by and, at one point, open only to insurance groups. Since then, membership in the organization has ballooned, numbering 50,000 manufacturers, engineers, installers, elected officials and others concerned with the protection of life and property. What was once a small, largely volunteer organization with a staff of six is now a non-profit with a surplus in excess of $200 million dollars and home to some of Massachusetts’ most highly-paid nonprofit executives.

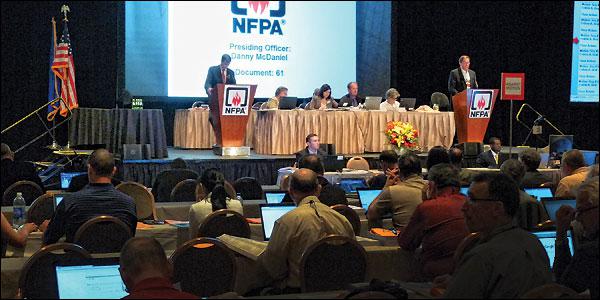

Codes are made in a standards-development process where any of the NFPA’s rank-and-file members can participate. Anyone—member or not—can suggest new code or changes to code during public comment periods. But, influence is wielded largely by a handful of appointed technical committees, who respond to public comments and choose which revisions to pursue. Committee members include people with all sorts of interests: manufacturers, installers, labor unions, government officials, researchers, insurers, special experts, and anyone who uses fire safety products. Membership in NFPA’s top standard-setting body—the standards council—include former manufacturing executives, leaders of standards-setting organizations, the American steel lobby, and former fire engineers.

Most of the NFPA’s 300 standards are revised and eventually published on a three-year cycle. These ongoing revisions are what makes the NFPA the influential group it is: sales of publications make up the largest share of the NFPA’s budget, bringing in $41 million dollars from code books in 2015, with millions of that share funded by taxpayers.

The NFPA, like other standards-development organizations, has been criticized for providing a level of access that pales in comparison with the open meetings held by local governments and regulatory bodies. For all the effort and expertise that goes into developing code, incorporation by reference—the process that makes code into law—means that governments often adopt large parts of these codes wholesale, giving the industries and membership of the NFPA a sizable influence over what becomes law.

Code sometimes becomes a battleground between special interest groups. The Supreme Court found that a manufacturer recruited hundreds of new NFPA members to vote on a standard undermining the makers of plastic conduit. Plumbers have been accused of lobbying against plastic pipe to contain the rise of DIY renovation. While anyone can become a member, individuals and small businesses may lack the resources necessary to participate in the numerous meetings where standards are developed and confirmed.

NFPA: How You Can Get Involved

NFPA meeting (Image Credit)

In the end, the NFPA’s code development process allows anybody to participate and, ultimately, depends on the efforts of more than 9,000 committee members and an even larger membership. If you’d like to take part in a process dedicated to preserving life and property in all 50 states, the NFPA welcomes your involvement in a variety of ways.

If you’d like to see changes made to a particular code, you can contribute in one of two stages in the code-making process: the public input stage and the public comment stage.

During the public input phase, the NFPA invites any suggestion, whether a revision or new code. They’ve detailed this process here.

On the other hand, the public comment stage allows suggestions on proposed drafts. You can learn more about that process and participate here.

For those looking to get more deeply involved, membership is open to anybody at rates as low as $445.00 for three years. Members have voting privileges, discounts on code books, subscription to regular NFPA publications, and one-on-one help with standards questions. If you’re interested in joining one of the nation’s most influential code-setting bodies, click here.

Full transparency: QRFS makes nothing off the NFPA links above. We simply believe if you must live within a regulation – even one as successful as the U.S. fire code – you should know how to influence it.